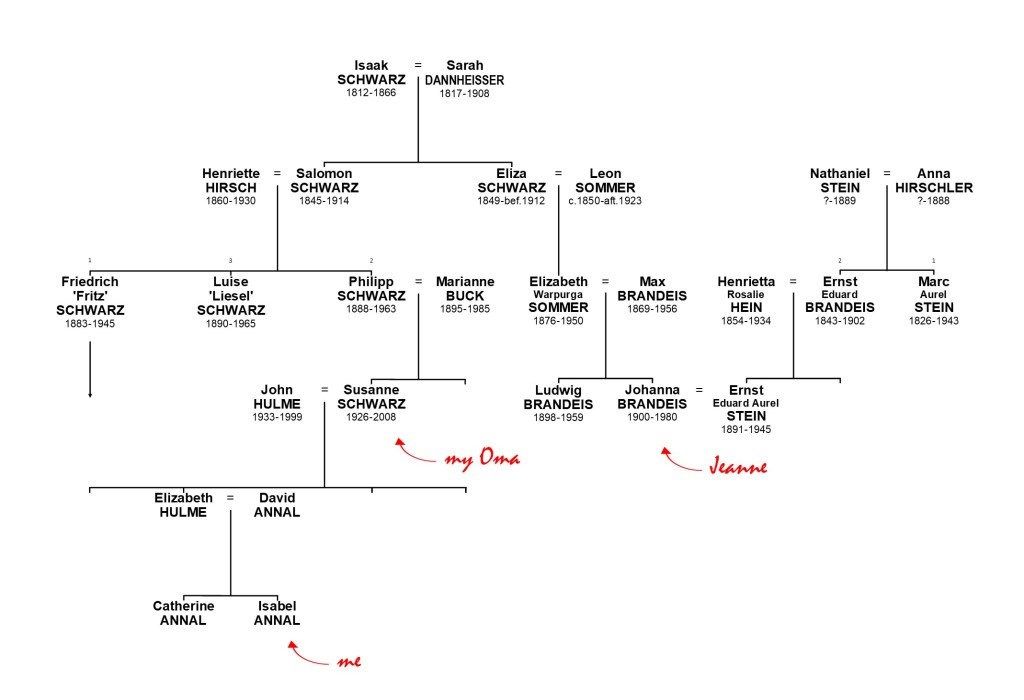

I’ve been planning today’s blog for a long time. I want to tell the story of ‘Aunty’ Jeanne, a woman whose World War 2 experience has always fascinated me, but it feels like there’s so much I don’t know. Jeanne and her husband didn’t have children – like many other Jewish couples in central Europe at the time, they were probably wary of the world that their offspring would have to live in. So, although we’re fairly distantly related – she’s my second cousin twice removed – I’ve ended up with some really important documents from her life. The most interesting of these are several passports and visas, which trace her and her husband’s movement around Europe, fleeing Nazi persecution. For a couple of years they even lived under fake identities.

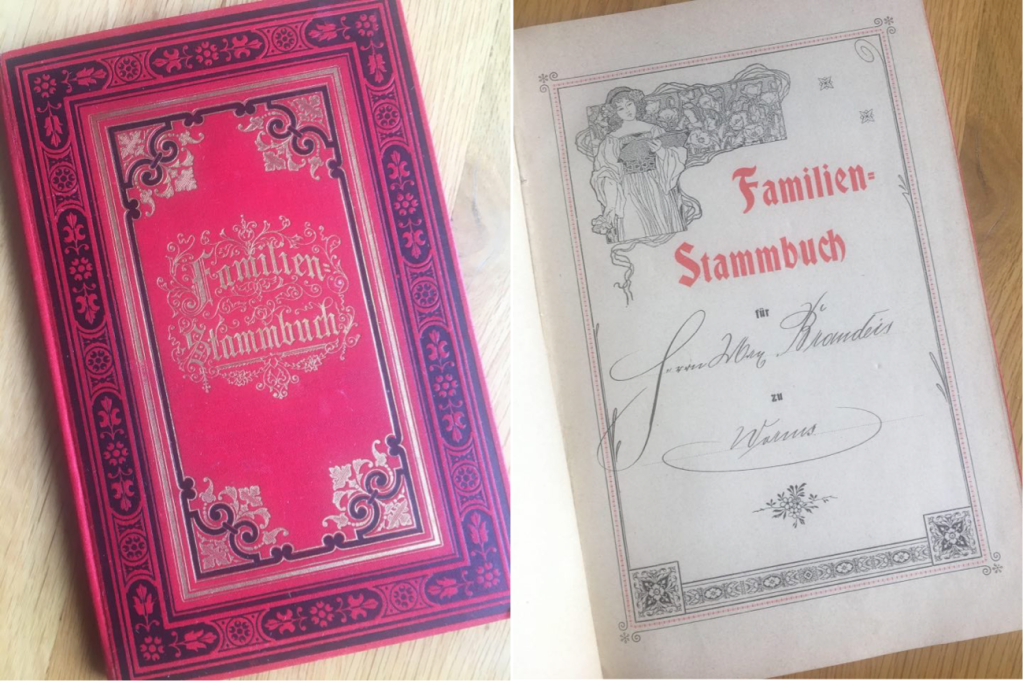

Johanna Brandeis was born to Max and Elisabeth Brandeis (née Sommer) in 1900 in Worms, Germany. As far as I know, she was in Germany until her marriage some time before 1932, but I don’t really have any information about her life in its first three decades. We’ve inherited her beautiful Familien Stammbuch, traditionally used by Germans to record their lineage, and exploited by the Nazis to determine who ‘counted’ as a German citizen under the terms of the Nuremberg Laws. Sadly, Jeanne’s Stammbuch only contains entries for her parents, her, and her older brother, Ludwig. I assume Jeanne went to university, because she was well educated; she spoke several languages and loved literature.

Her husband, Ernest Eduard Aurel Stein (Ernst) was born to Ernst Eduard and Henriette Rosalie Stein (née Hein) in 1891 in Jaworzno, near Krakow – then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In part 2 of this blog I’ll focus more on Ernst’s life, but there are some documents I need to track down before I can write that.

Ernst’s father’s brother, Márk Aurél Stein, was an eminent archaeologist who made several very important discoveries in Central Asia. As an archaeologist myself, this connection – however distant – is very exciting. Aurel, being childless, appears to have grown very close to his nephew Ernst, who was himself a Byzantine and Late Antique historian. Some of the little information I know about Jeanne’s experiences in World War 2 comes from letters written to her and Ernst by Aurel. There will definitely be a Sir Aurel Stein blog in the future.

I don’t know where, when or how Jeanne and Ernst met, but they married in April 1923 in Vienna, where Ernst was a lecturer at the University. He worked in Frankfurt am Main at the Römisch-Germanische Kommission from 1927 to 1931, and then moved to the University of Berlin. Sadly I have no idea what Jeanne herself was doing during this time – probably she was a housewife. I can only imagine that the Jewish couple watched the rise of Nazism with a mixture of fear and disgust. I recently learned that Ernst, under the pseudonym Gottlieb Hellseher, had written an anti-Nazi article in 1932, entitled ‘Un projecteur sur l’Allemagne’ (A Spotlight on Germany). Needless to say I was very excited to find out about this, and even more excited that the British Library have a copy of the magazine it was published in! Unfortunately, I won’t be able to see it until the current lockdown is lifted, so look out for part 2. After the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933, Ernst quit his role at the University of Berlin, and he and Jeanne fled Germany. I think this was the last time Jeanne was ever in the country she was born in.

In July 1933 Jeanne and Ernst were granted authorisation to live in Belgium permanently, where Ernst taught as a visiting professor in Brussels. At this time Jeanne had taken on Ernst’s Austrian citizenship (at the time Krakow counted as Austrian because it was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Will I ever get to grips with the geo-political make-up of Europe pre-WW2? Probably not.) Ernst was also a visiting professor at the Catholic University in Washington DC, and I have Immigrant Identification Cards allowing him and Jeanne to travel to America, issued by the American Consulate at Antwerp, Belgium in August 1934. They appear on passenger lists sailing from Antwerp to New York twice – on 7th September 1934 (arriving 17th), and on 15th September 1935 (arriving 27th). On both lists Ernst’s profession is Professor, and Jeanne’s is Housewife.

In the 1934 document both Ernst and Jeanne say that they read and write French and English. In 1935 Ernst, perhaps feeling less modest, lists French, English, German, Italian and Greek, while Jeanne lists French, English and German. Interestingly, while Jeanne’s record says ‘German’ under the ‘Race or people’ column, Ernst’s says ‘Hebrew’ in 1934. On the 1935 document both give their race as German. In 1934 the pair state that they expect to stay in the United States for 1 year. The 1935 record shows that their last permanent residence was in Washington DC, having lived there until May that year. This time they are planning on staying indefinitely which, in hindsight, would probably have been a good idea.

I don’t know exactly when Jeanne and Ernst returned to Belgium, but in a much later letter from Ernst’s uncle, Aurel Stein, he reveals that, due to Ernst’s “physical strength” he had “felt induced to leave [his] academic post across the Atlantic”. In 1937, Ernst was appointed professor of Byzantine History at the University of Louvain, and the couple, as far as I can tell, lived there for a few years.

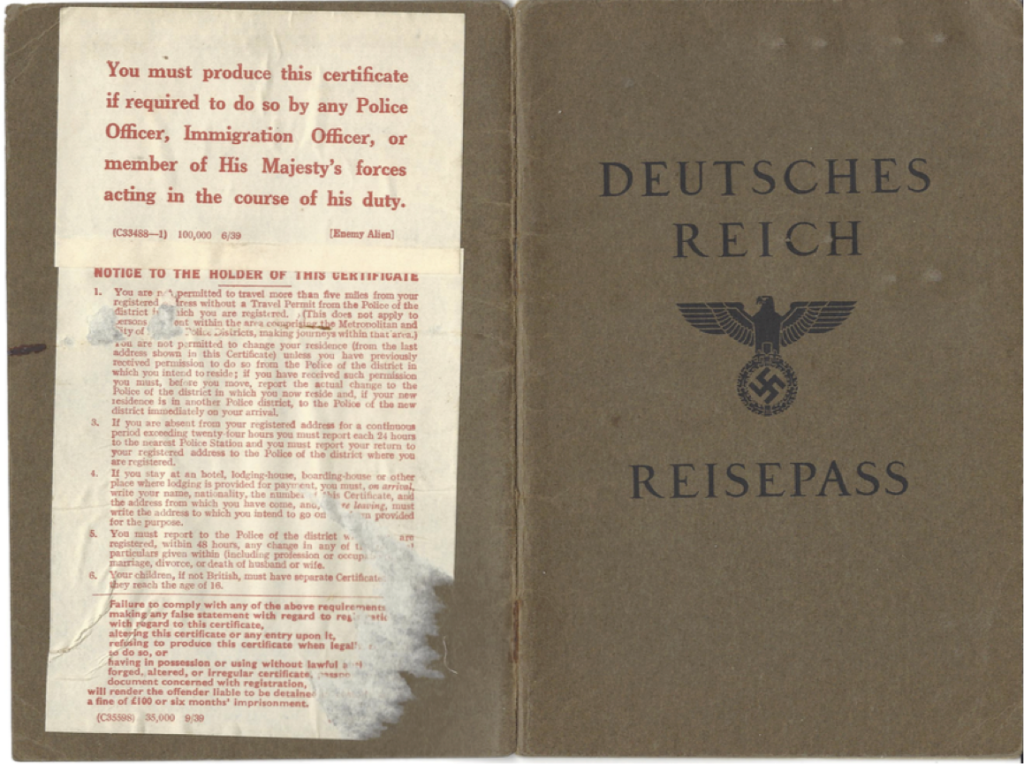

Max and Elisabeth Brandeis, Jeanne’s parents, managed to leave Germany in 1939. I have their English passports, with their ‘Enemy Alien’ certificates stapled to the back. Jeanne’s brother, Ludwig, also sought refuge in Britain in the late 1930s, with his wife, Ingeborg, and their daughter Charlotte (born in Frankfurt, 1926). Ludwig Brandeis changed his name to Lawrence Brandon, and became a naturalised British citizen in 1946. I don’t know how much (if at all) they were in contact with Jeanne for almost a decade while she moved around Europe.

I sent my dad down a rabbit hole researching this line of the family – it’s definitely useful to have a professional genealogist on hand. Ludwig and Ingeborg divorced some time after they moved to Britain. My dad found Max, Elisabeth, Ingeborg and Ludwig’s Internment Exemption Certificates from 1939. One of the questions they were asked was whether they wanted to be repatriated and, unsurprisingly, they all said no. As ‘enemy aliens’ they were exempt from internment, I assume because they were Jewish refugees, but we also learnt from these certificates that Ludwig was even “exempt from registration, while serving in HM Forces”. We didn’t know that he had served in the British Army during World War 2, but this explains why, in late 1945, an English soldier called Kenneth Ward showed up at my Oma’s house in Berlin. Kenneth’s Jewish parents had sent him and his brother to England just before the war, and Ludwig had asked his friend to look for his mother’s cousin, Philipp Schwarz (my Oma’s father). Kenneth gave the family tobacco and chocolate –valuable goods at the time in Berlin – which they were able to trade for very scarce, nourishing food.

Anyway, back to Jeanne and Ernst. In September 1940, Aurel Stein wrote to Jeanne in response to a letter from her on 30th May the same year. His letter hints at dramatic events for the couple – that Jeanne and Ernst had “left [their] home under such harassing circumstances”, and faced “those great trials & fatigues on [their] journey through France”. On 10th May 1940, Nazi troops invaded Belgium, and less than three weeks later the country was officially under German occupation. Whether Jeanne and Ernst had foreseen Belgium’s conquest earlier than May, or had fled when the country was invaded, they were lucky to have escaped when they did. In 1940 they were, according to a later letter from Aurel, in Montpellier, France, and since they were wary of the “uncertain” future at Louvain University, were hoping Aurel could help Ernst once more “to secure some academic post in the U.S”. I desperately wish I had the letters Jeanne and Ernst had written to Aurel, not just his replies.

Aurel also mentions “the kind friend of Ernest who has offered such generous hospitality to you both”. I think the friend he’s referring to was Monsieur l’Abbé, perhaps the interestingly dressed man in this unlabelled photograph of Jeanne and Ernst. I have a few letters back and forth between him and Jeanne after the war, which I will fully translate from French soon (read: ask my mum to translate), and include in part 2. I already know from one of these letters, though, that the couple trusted Monsieur l’Abbé enough to tell him their true identities, which they were hiding from everyone else.

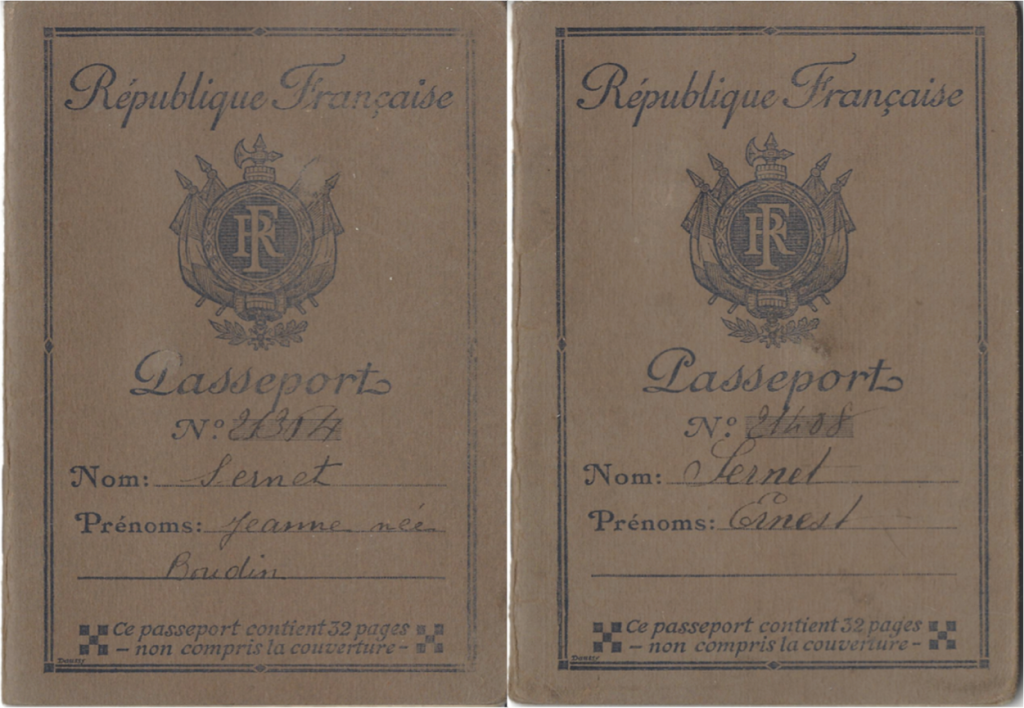

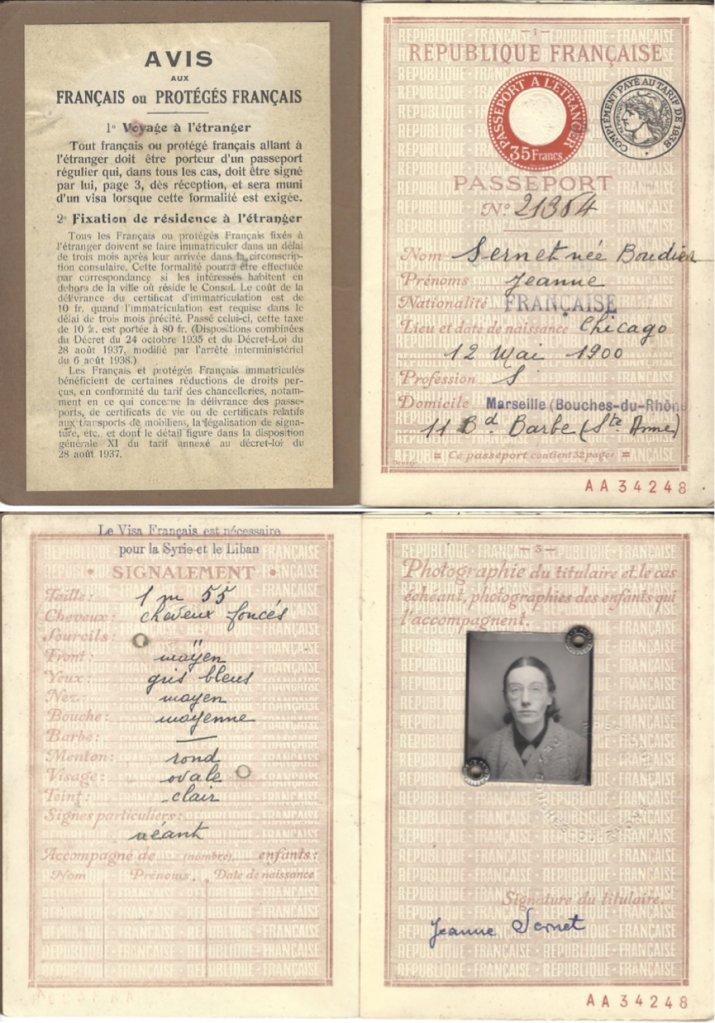

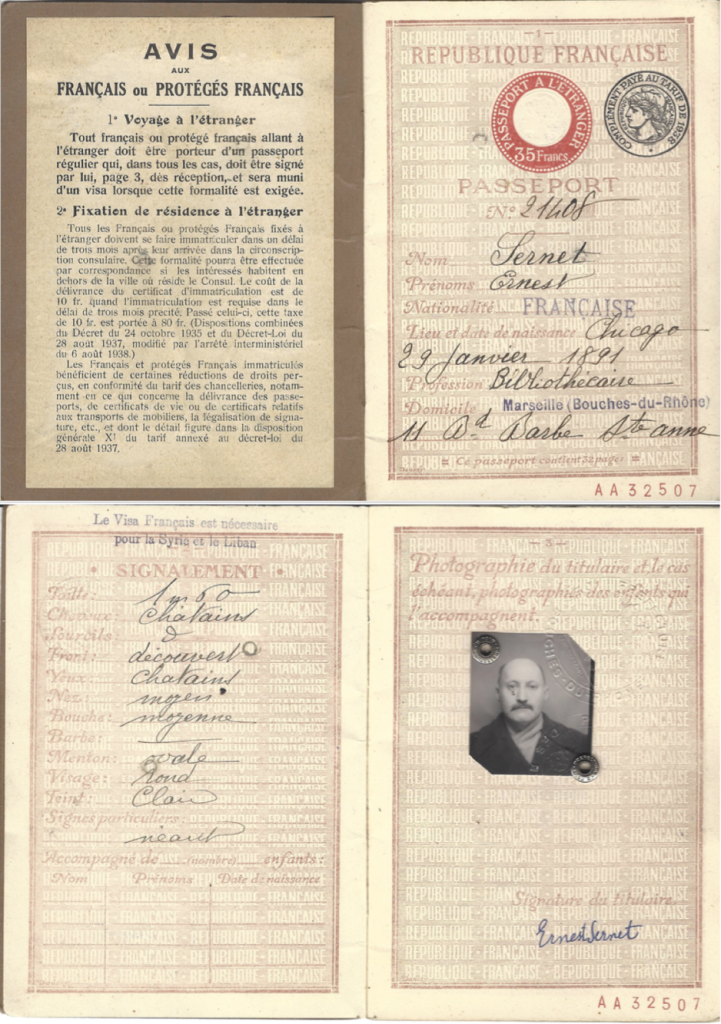

In late 1940 Jeanne and Ernst were living in Vichy France (the ‘Free Zone’), as far as I can tell, in Marseille, going by fake names. In November of that year they were issued French passports under these aliases. They called themselves Ernest and Jeanne Sernet (née Boudier), and claimed to be French nationals, though both born in Chicago. Jeanne Sernet has the same date of birth as Johanna Stein, but Ernst Sernet’s birthday is given as 29th January 1891, although Ernst Stein was actually born on 29th September 1891. Ernst lists his profession as Bibliothécaire (librarian), and Jeanne has no profession. Their passports were both stamped twice with authorisations to travel to Syria, once in December 1940, and again in March 1941. I assume that these stamps mean that they did indeed travel to and from Syria twice under these false identities, presumably for Ernst’s work. It was probably around this time that Johanna privately stopped going by her German name, opting instead for the French ‘Jeanne’. She never returned to Germany, and was reluctant later even to speak the language with family.

The next record I have of Ernst and Jeanne ‘Sernet’ is in the form of identity cards issued in Grenoble, France in November 1941. Their (fake) details are the same as those on their passports. Ernst is still a librarian, and Jeanne is now a Professeur privé (private tutor?). She looks old in this photo. She was never beautifully photogenic (sorry Jeanne), and perhaps it’s more to do with the lighting, but she looks to me like she’s been through a lot. And Ernst appears to have lost quite a bit of weight. On the back of these identity cards it’s recorded that the couple moved house on 16th April 1942, and again on 6th May 1942. This period from 1940 to 1943, when the pair were constantly on the move and living under aliases, is the one I’d most like to find out more about. How much danger were they really in on a day-to-day basis? Did many people they met in France know their true identities? Were they hoping to see out the war in France?

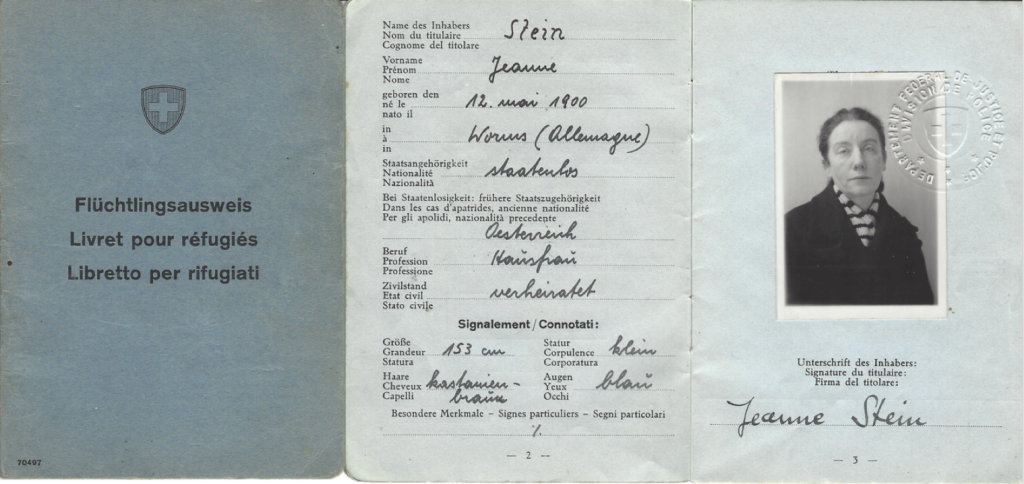

Whatever they had planned, either the situation became too dangerous, or perhaps the opportunity they had been waiting for finally arrived, and Jeanne and Ernst fled to Switzerland, arriving on 20th January 1943. I have Jeanne’s Flüchtlingsausweis (refugee ID) issued in Geneva in May 1945. Maybe it’s because she’s taken her glasses off, but she looks exhausted in this photo. She’s back to being Jeanne Stein, a Hausfrau born in Worms, though for her nationality she’s put staatenlos (stateless). In a letter Aurel Stein wrote at this time, he talks about “Jeanne’s devoted care”, and refers to her as “brave Jeanne”. That’s certainly the impression I get of her – she supported Ernst vehemently, and had probably completely exhausted herself getting them both to safety (this is no criticism of Ernst, he had clearly been ill since their time in America, and everybody reacts to traumatic situations differently). I don’t have any documents for Ernst from this time, although I know that he lived with Jeanne and taught in Geneva until his death there in February 1945. He died before the war ended, never getting to see the Nazis defeated.

Jeanne appears to have stayed in Switzerland until April 1945, collecting her rationing cards every month except for the February that Ernst died. She returned to Belgium, and was baptised as a Roman Catholic in Melsbroek in November 1945. A letter from Berne in October 1947 recognises and thanks her for “collaborating voluntarily at the press service of the Belgian Legation in Bern from October 1943 to September 1944”. Another letter, this time from Brussels in April 1948, thanks her and Ernst for their assistance in Belgium’s war effort. In June 1948, Jeanne gave up her Austrian citizenship and became a Belgian citizen.

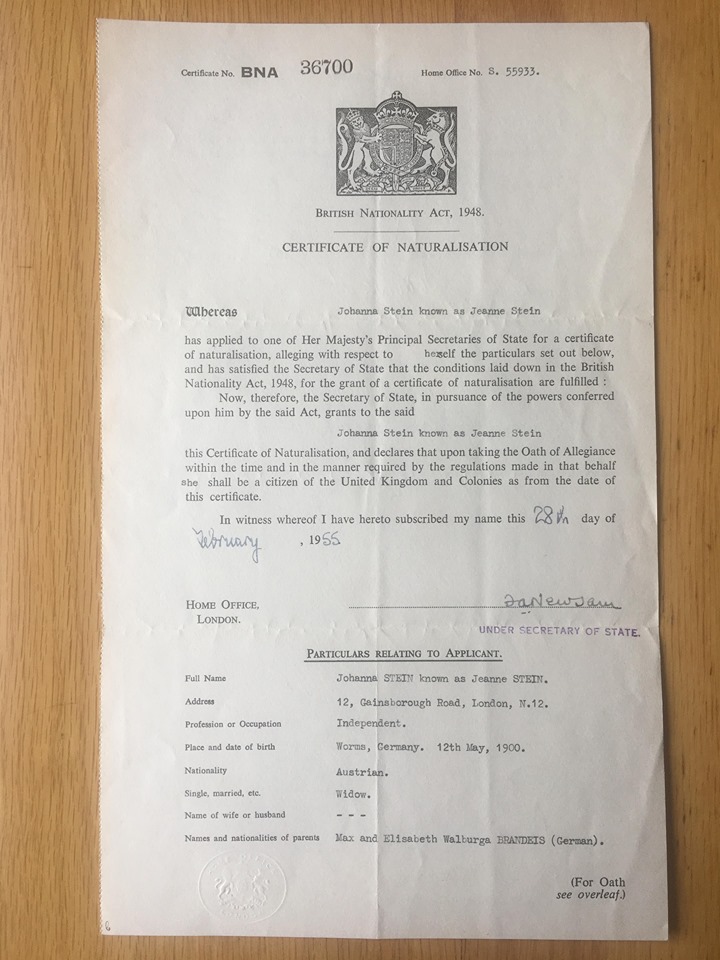

In 1949 Jeanne visited Britain, and at some point she moved to live in Finchley with her brother, Ludwig (Lawrence). In 1955 she became a British citizen. She worked tirelessly to get Ernst’s final book, Histoire du Bas-Empire volume 2,published. Jeanne is a family historian’s dream! She kept so many official documents and personal letters, all beautifully organised and labelled. Her British passports show that she travelled quite often – mainly to Belgium, Switzerland and the Netherlands. But she never returned to Germany.

In my Oma’s memoir she recounts how she first met up with Jeanne and her family in England after the war:

“Quite amazingly I recognized Jeanne’s brother Ludwig one day at a Cezanne exhibition in the Tate Gallery, although I had last seen him in Berlin 16 years before. I knew that they lived in London and perhaps I was unconsciously looking out for them … Both Ludwig and Jeanne were very kind to me and made me feel welcome.”

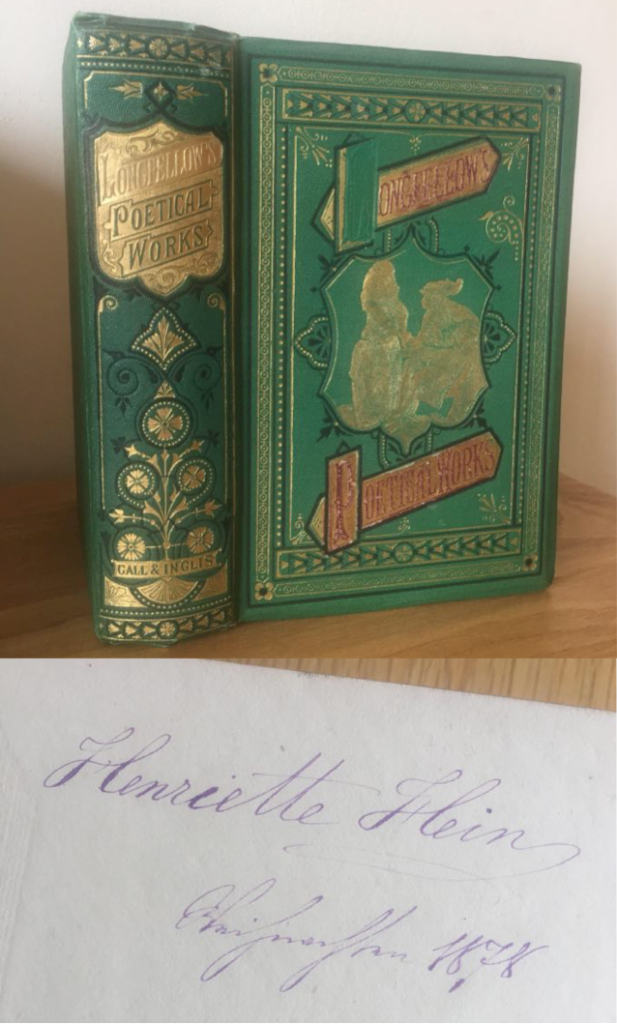

From my Oma’s diaries in the late 1950s and early 1960s it’s clear that she and Jeanne were very close. Jeanne came round a lot to help Susanne with her four young children, and I’m sure it was important for both women to be around someone who could really empathise with what they had experienced. My mum and her siblings grew up with regular visits from ‘Aunty Jeanne’, who often brought round homemade German cheesecakes. We have a few beautiful books my mum inherited from her. My favourite – a collection of Longfellow’s Poems – originally belonged to Ernst’s mother, Henriette, and was given to her in 1878.

Jeanne died in Finchley Memorial Hospital in 1980. I wish I had been able to meet her, and to ask her more about herself.

What an astonishing amount of detailed research, I am staggered at how much information you have uncovered and the pain staking detail you have produced, it’s one of the finest pieces of research I have ever seen. You are definitely a chip of the old block as they say.

LikeLike

Thanks Paul! It took such a long time to work all of this out 😅

LikeLike

This is one of the most detailed and thoroughly well researched pieces of work that I have seen. The amount of detail is astonishing. You should be suitably proud of this wonderful piece of work and you can see that you are definitely a chip off the old block!

LikeLike

Very lovely post.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi

I have been working on the tandem tree showing the Austro=Hungarian ancestry of Nathan (Nathaniel) Stein for a someone who believes she could be related, but is looking for a family connection. Nathaniel appears on the fringes of your tree, so I have found the information you have provided highly informative, aiding my research tremendously. I would also like to make a couple of copies of Stein family images from your research to enhance my presentation, but feel that it is only polite to ask you first. So can I?

Regards Roy

LikeLike

Hi Roy,

Is the Nathaniel you’re researching the grandfather of my Ernst? I’d be interested to know any information you have on him, as that’s not a branch of the tree I know much about.

You’re very welcome to use anything from my blog, especially if it is for other relatives 🙂

LikeLike