I spent a while thinking about what blog I would write for Holocaust Memorial Day. The theme this year is ‘Be the Light in the Darkness’. The blog I posted in February last year, about the different ways people helped my Oma’s family, would have been perfect for it. When I looked down my list of blog ideas there weren’t many ‘light’ topics there. But I think this blog fits, and it’s one I’ve wanted to write for a long time. It’s about my Oma’s aunt – her favourite relative – who she described as “a person of great sensitivity and artistic feeling”. Her full name was Luise Karolina Schwarz, but everybody called her Liesel. To my Oma, to my mum, and to me, she is Tante Liesel. In fact, as a child (before I knew that ‘Tante’ meant ‘Aunt’) I actually thought her name was ‘Tanteliesel’. This is her story.

Luise Karolina Schwarz was born on 3rd September 1890, to Henrietta and Salomon Schwarz. She had two older brothers, Friedrich ‘Fritz’ (born 1883, whose life you can read about here), and my great-grandfather, Philipp (born 1888). My Oma, Susanne, recalled that she was “especially devoted to her brother Philipp”. Liesel never married, or had children, but she clearly loved her nieces and nephews. In her memoir, Susanne wrote fondly about Liesel:

“With her strong feeling for children and young people, and her happy sense of humour, she was always a favourite aunt to us children”.

Liesel studied Kunstgewerbe at the Königliche Kunstgewerbeschule München (Royal School of Arts and Crafts) in Munich. She specialised in weaving, and had her own loom in her home in Landau. I’m sure that my Oma’s subsequent career as an artist owed a lot to Tanta Liesel’s influence. In fact, in with all the family photos and official documents, we have an envelope, which holds three little pieces of art that Susanne had made for Liesel as a child. One of them was sent to Liesel on her 42nd birthday, when my Oma was six years old. Susanne wrote in her memoir about how much her mother “encouraged us to draw and make things, and she kept and dated all our early ‘works’, though sadly these were lost in the war”. So I think it must have meant a lot to her that Liesel had kept these little creations from her childhood.

Though Liesel’s main passion was art, she was also a keen cook. Susanne recalls in her memoir the happy times that she and her father spent in Landau during the summer holidays:

“In Landau Tante Liesel worked hard to make it a nice holiday for us, especially with her cooking. She was very good at spoiling her brother and me.”

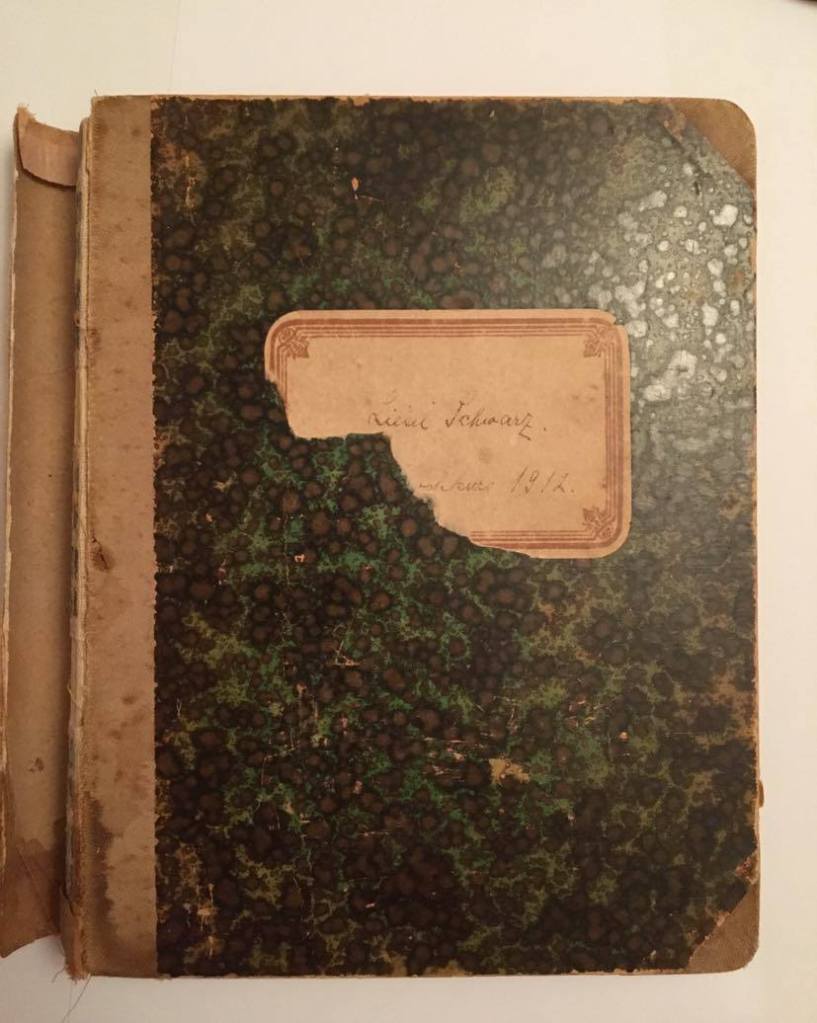

Probably my most prized possession is Liesel’s handwritten recipe book. It reminds me so much of something I would make (i.e. ridiculously over the top and time-consuming).

The book begins on Montag, den 4. November 1912. She wrote out the Speisezettel (menu): Reissuppe; Ochsenfleisch mit Meerrettig u. Zwiebelbeiguss, Kalbsbraten mit gebratenen Kartoffeln und Salat; Haselnusscrême (rice soup; ox meat with horseradish and onion glaze, roast veal with fried potatoes and salad; hazelnut cream), and then the recipes for each of these dishes. She notes that the recipes are right for six people – her, her two brothers, their parents and (unless I’m forgetting somebody obvious) another unknown person.

She writes out the menu and recipes for most days until Mittwoch, den 11. Dezember 1912: Gebackene Griesklöschensuppe; Hummer-Mayonnaise; Schnitzel àla Holstein mit Sauce béarnaise; Pfirsich-Rahmschnee (baked semolina dumpling soup; lobster mayonnaise, escalopes à la Holstein with béarnaise sauce; peach cream mousse). The last 20 or so pages are taken up by an index, with a section for ‘Suppen’ a section for ‘Fleischspeisen’, a section for ‘Torten’, etc. She’s numbered every page of the book and indexed each recipe in the relevant section. As a vegetarian, I’m absolutely horrified by most of the meals, but the book is one of my favourite things in the world. My only worry is, if this only covers November to December 1912, how many others were there?

Liesel was very close to her mother, Henriette. Her father, Salomon, died in 1914, when Liesel was only 24. My great-grandfather, Philipp, married Marianne in 1924, and moved to Bad Dürkheim. Fritz, the oldest brother, was married to Babette (who had been the family’s cook) and his family lived on the top floor of the house. This left Luise, who never married, living in the first floor of the house with her mother until Henriette’s death in 1930. In her Will Henriette wrote of Liesel:

“I am giving preference to my daughter Liesel because she cared for me for many years while I was unwell, denying herself and sacrificing herself for me. She was always there for me and always in her loving way had only my well-being in mind. May she find the reward for it that she deserves”

We think the two people you can see in this photo, in the first floor window of the family house (to the left of the statue), are probably Liesel and Henriette.

The family seem to have been a respected and well-liked part of the community up until the 1930s. Salomon’s business, which Fritz had taken over, was doing well, and in Landau’s 1932 address book Liesel is listed as a Kunstgewerblerin (a craftswoman). Yet, as I discussed in my blog post about Fritz, support for the Nazis in Landau was high, and the majority of the Jewish population left the small town by the end of the 1930s. At some point near the end of the decade, a Nazi party member, Fräulein Eberhardt, was moved into a small apartment in the family’s house. The Nazis made sure that there was a loyal party member keeping an eye on every house in Germany, to ensure that no ‘crimes’ would go unreported. Some time later in the late 1930s, 18 of the remaining Jewish residents of Landau were forced to move into one house; Luise, her brother Fritz, and Fritz’s daughter Anna, were three of those moved to Kaufhausgasse 9.

Early in the morning of 22nd October 1940, Gestapo officials, members of the Gendarmerie and policemen broke into Kaufhausgasse 9. They instructed the Jewish men, women and children living there to prepare to leave; they were to gather up any wealth or property they had left, and hand it over to the Saar-Palatinate Auffanggesellschaft. Then the Jews from Landau (aged between 3 and 83) and the surrounding area were taken to Landau’s railway station, where they were loaded onto trains. Fritz, supposedly a ‘privileged Jew’, and Anna, a Mischling, weren’t taken that day (although Fritz did eventually get deported to Theresienstadt – proof that whether or not ‘privileged Jew’ status counted for anything was completely dependent on the whims of local administrators). Did the Gestapo have a list of those they were supposed to take? Or did Fritz have to show some documentation to stop them from taking him and Anna? There would have been nothing he could do to stop them from taking his younger sister.

Across the Palatinate, Baden and Saarland, a total of 6,557 Jews had been rounded up that day. They were handed over to the French Vichy Government, and taken to Oloron-Sainte-Marie, a place on the edge of the Pyrenees, 15 kilometres northwest of the small town of Gurs. A small camp had been established there in 1939, originally to house the roughly 700 Civil War refugees from Spain. By the time that Liesel and the other southwest German Jews arrived, several thousand Jewish emigrants from Germany and Austria, who had fled to France, Belgium and the Netherlands before the outbreak of World War 2, had been arrested as hostile foreigners and also interred at Gurs. Within a few days there were around 13,000 prisoners living in the barracks.

Gurs was neither a work camp, nor an extermination camp, and the French guards were, supposedly, not particularly malicious or violent towards their prisoners. Still, the windowless huts that the inmates slept in offered no insulation, and didn’t even keep out the rain. Up to 60 people were forced to sleep on sacks of straw on the floor, in cabins measuring only 25m2. There was never enough food to go around, and certainly nothing nutritious. Gurs had no sanitation and no running water. Unsurprisingly, the camp was rife with illnesses, particularly dysentery and typhus, and the death rate was high.

I mentioned in my blog about Fritz that one of my main sources of information about the family –‘Juden in Landau’ by the Stadt Landau Archiv und Museum – contains several inaccuracies. So, although the book states that 34 Jews were deported from Landau to Gurs on 22nd October, I believe the number to be slightly higher. Of the 34 listed in the book, 11 died in Gurs, most in the first few months after they arrived. 19 were moved to other nearby camps, or to Auschwitz, where they were murdered, or died from the awful conditions. Luise was one of only four of the 34 Jews taken that day from Landau who survived the war. Otto Brunner (born 1895) was moved to a camp at Les Milles on 25th October 1941, and the next day managed to leave for the USA. Mina Sender (born 1876) was one of only 48 Jews never deported from Gurs, and survived there until late 1944, when France was liberated. She lived the rest of her life in Strasbourg. Sophie Samson (born 1879) was transported to Noé in January 1941, and survived there until September 1944, before moving to London to live with her daughter.

Perhaps the strangest thing about Gurs was that, unlike other Nazi camps, it wasn’t particularly well guarded. The surrounding barbed-wire fences, which were not electrified, were only two metres high, and there were no lookout towers. So it was not uncommon for prisoners to attempt escape, usually heading for Spain. Most of those who tried to flee, having no money, food or decent clothes, were soon found and returned to the camp. Between 1940 and 1944 a total of 755 prisoners managed to escape Gurs. One of these was Liesel.

According to my Oma’s memoir, Liesel’s escape went something like this:

“just before the Jewish prisoners were transported to Auschwitz in 1942 she managed to escape, together with about 20 other women. Having crossed southern France they reached the Swiss border near Geneva, but were then turned back by the Swiss guards – all except Tante Liesel, who was allowed to cross because she was seriously ill”

I’m sorry that I don’t know these other women’s names. And I don’t want to present this story as some sort of miracle, because for the other 20 women I doubt that there was a happy ending. They took a huge risk, sneaking out of the camp “bei Nacht und Nebel” (at night and in fog), as one relative recently described it to me. They must all have been malnourished, and the journey to the Swiss border would have been physically exhausting – not to mention the emotional toll it must have taken.

The Swiss archives have a record of Liesel (who they’ve called Louise Caroline Schwarz) arriving illegally in Switzerland on 28th September 1942. I’ve applied to see the original, and now I’m just waiting for them to digitise it for me (although I don’t think there’s any extra information on it). One thing that’s really puzzled me while I’ve been researching Liesel’s story is how much my Oma and her parents knew about what was happening. In her memoir, Susanne wrote:

“Some time in the summer of 1945 we heard that Tante Liesel was alive in Switzerland”

So I had always assumed that, after she was deported in 1940, and until the end of the war, Liesel’s family didn’t know where she was, or whether she was even alive. But then, when I was preparing to write this blog, I searched ‘Liesel’ in the digitised version of my Oma’s 1943 diary (thanks to my mum for sorting that out), and there are a few mentions of writing letters to Tante Liesel. Susanne even records getting a card back from her on 17th February 1944!

I’d like to find out what life was like for Jewish refugees in Switzerland. I imagine Liesel must have spent some time in a hospital when she first arrived. I know that she lived for a while in some sort of refugee camp in Ticino, near Lake Lugano. I believe she lived in Bern for the next few years, but I have no real idea of what her life was like there.

I recently found a document in the Swiss Federal Archives entitled ‘Liste der deutschen Zivilfluchtlinge, die nach Deutschland (englische Zone) zuruckzukehren wunschen’ (List of German civil refugees who wish to return to Germany (English Zone)). It’s in a folder, dated 1943-1945, containing 66 documents related to a man called Paul Meuter (born 1903), who appears to have been a Communist refugee in Switzerland. This particular document doesn’t have a date on it, but since it refers to the English Zone, it can’t have been written before the summer of 1945. Liesel’s name is on this list. She’s said that she wants to return either to Landau, or to Berlin. It made me really emotional to see that she had put Berlin as an option – she must have been thinking about being close to her brother and his family. I was also surprised to see that she had wanted to go back to Germany so soon.

Liesel eventually returned to Landau on 13th March 1951. I can’t imagine how it felt to return to that house. The Nazi party member who had been installed to keep an eye on the residents still lived there. My mum remembers meeting Fräulein Eberhardt in the 1970s; the family were on civil terms with her and there was no evidence of any ill-feeling. When my mum stayed in the house as a child, she had to go through Fräulein Eberhardt’s flat to get to the toilet. This was particularly intimidating, because she kept an axe tied up above her door to deal with any unwanted intruders.

Sometimes when I’m in Landau, on the Platz, I think of the photos I’ve seen of the buildings covered in Nazi flags, and I feel sick. How could Liesel go back there? In August 1935 she must have read the notices saying ‘Jews not wanted here’, which were plastered around the town. She heard the shop windows smashing and saw the synagogue burnt down on the night of November 9th 1938. She witnessed the SA marching down her street repeatedly. And in 1940 she was taken from her bed by armed men, to be imprisoned without having committed a crime. But Landau was her home, and she loved it.

Liesel died on 18th October 1966. Her grave is one of the very last ones in the Jewish section of Landau’s Friedhof. It’s incredibly moving to see the empty space where the local Jewish population would have been buried, if they had just been allowed to live out their natural lives in Landau. Against all odds, Liesel was buried in the town that she loved, close to her parents.

A Stolperstein for Liesel was laid outside the family house on the Platz in Landau, next to the one for her brother, Fritz. The stone was sponsored by a woman from the Markt (which comes to the Platz twice a week) who remembered Liesel fondly.

If I could choose to meet just one relative, it would be Tante Liesel. This Holocaust Memorial Day I am remembering her, a light in the darkness.

Further Reading:

Kohl-Langer, C. et al. 2004. Juden in Landau: Beiträge zur Geschichte einer Minderheit. Landau: Stadt Landau in der Pfalz, Archiv und Museum

Another beautifully told story, you chose wisely for Holocaust Day, Tante Liesel’s Story is filled with so many different emotions, fear, hatred, survival, and above all else hope. The picture of you at the grave was very moving, she would be immensely proud of you for telling her story

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would like to reblog this story but would only do that with your permission

LikeLike

Go ahead! The more people who read it the better 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was hoping you would say that, it’s such a powerful story and needs to be shared and told, thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just reposted it, forgot to,say how wonderful to have the recipe book as well

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know! I’m going to get around to making some of the less meaty episodes one day soon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes definitely! You should to make some veggie variations

LikeLike

Thank you Paul, that’s very kind

LikeLike

Hi Isabel – it is so wonderful that you have her recipe book. I’m very guilty of making those little homemade recipe books…. must run in the family? I’d be every so grateful if you could send some along. I’d love to try my hand at making some of them during lockdown 2.0 (3.0?). It’d also be a fantastic project to create a cookbook from her recipes!!! Deirdre.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Deirdre, it’s good to hear from you!

I’ve often thought about turning Liesel’s recipes into a proper cookbook, I’m just not sure how much of a market there is for dishes like ‘stuffed hearts’ these days? Anyway, I’d be very happy to send you recipes. Email me at isabelannal1878@gmail.com and we can sort out the best way of doing this

LikeLike

Amazing story. We were talking about the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC today. I have never been there but I have been to the one in Richmond Virginia. It is a horrific time. Tante Liesel was blessed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Isabelle. Enjoyed reading your bog. You’re a wonderful writer and I’m impressed as to the amount of information you have on our Schwarz family. Learning about our families experienes always breaks my heart. My father (Karl) must have learnt a great deal from Tante Luise as he was very good painter. Unfortunately I do not know what ever may have happened to all his artwork we had in our home not to mention those he did during the war. I was told stories of him hiding between floor boards, in Stuttgart, and painting in tight quarters to pass the time away. Thanks for doing so much research and sharing the story. I hope your family is well. Give my regards to your mum.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Henny! I’d love to know more about Karl. I’ve heard very few stories from that branch of the family, and it would be interesting to compare his and Anna’s experiences with my Oma’s.

Herzliche Grüße von uns allen x

LikeLike

Hi Isabel, I will send you and e-mail

LikeLiked by 1 person